Simon Ford, RCF’s Senior Director of Processing & Metallurgy, got an early start in metallurgy, working as a furnace operator for a steel company during his school vacations. Since then, his career has taken him around the world, conducting feasibility studies and metallurgical assessments for engineering firms and mining companies, including GenGold and Fluor.

Simon worked in operations on various gold mines in South Africa in the early part of his career before moving into engineering and process plant design. He has been involved in the entire life cycle of projects, having developed and managed test work programs, undertaken various levels of studies, and been involved in the design, construction, and commissioning management of numerous projects.

He has a Bachelor’s degree in Metallurgy and Minerals Process Engineering from the University of Witwatersrand (1990) and is a member of the Australian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (AusIMM). Simon joined Resource Capital Funds (RCF) as Manager of Metallurgy and Processing in 2014 and brings with him over 34 years of experience to the RCF technical team.

Simon recently took some time to chat with us about his work in metallurgical engineering and the role metallurgy plays in bringing metals out of the ground and onto the market.

In your own words, what is extractive metallurgy?

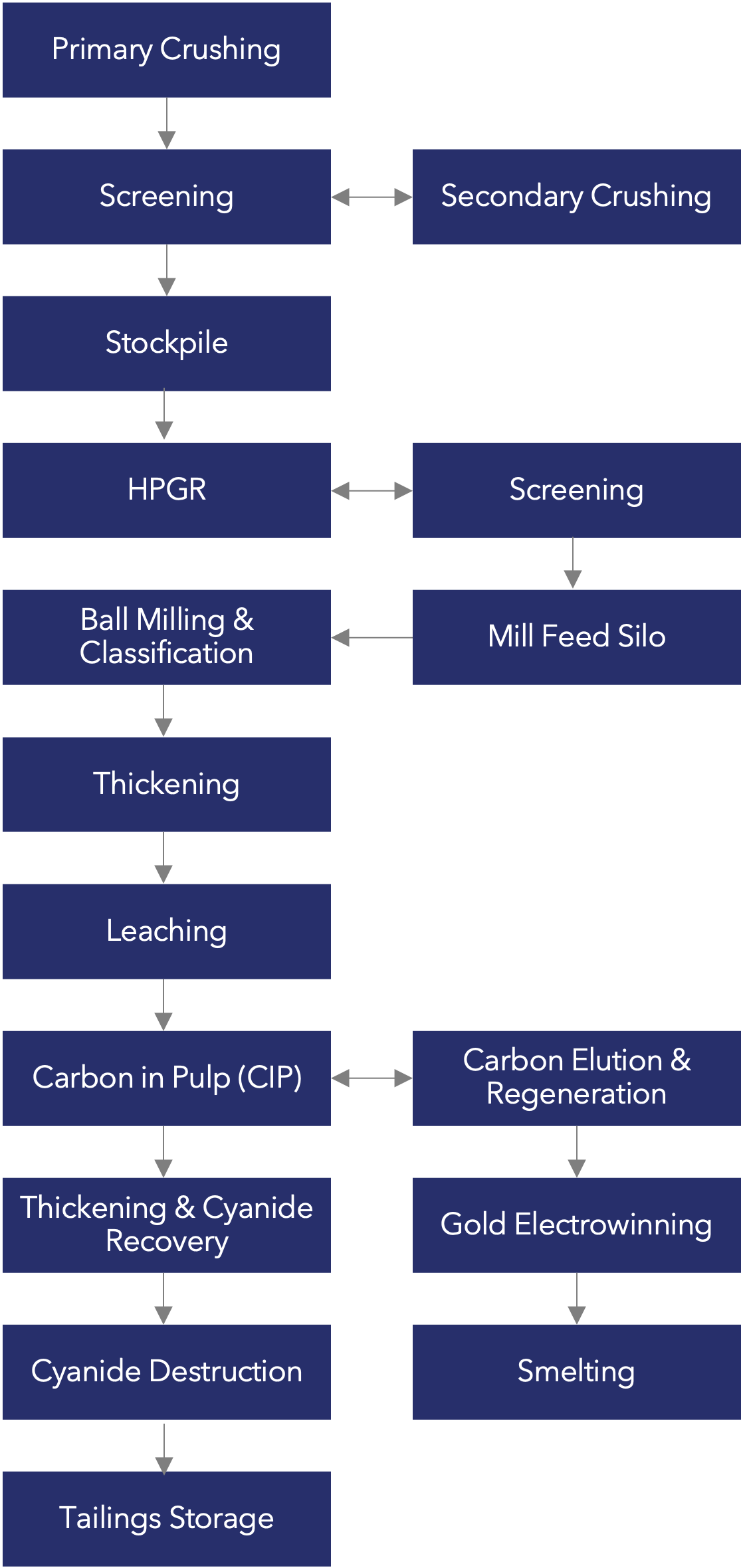

Extractive metallurgy is the economic extraction of metals or minerals from mineral deposits. This can be done using mineral processing, hydrometallurgy, pyrometallurgy, electrometallurgy, or a combination of these. The choice depends on what you are processing and whether you’re producing concentrates, intermediate products, or finished products.

In mineral processing, there’s no chemical transformation. You’re just using physical metallurgical techniques, like crushing and grinding to break the ore up and liberate the target minerals, then employing techniques such as gravity, flotation, or magnetic separation to separate minerals from the host ore.

Hydrometallurgy is a more complex process because you’re dissolving metals in solution to separate them. It often involves acids or bases, often temperature and pressure, and includes several processing stages. Pyrometallurgy is the use of heat to extract and purify metals. It most often involves roasting and/ or smelting. Electrometallurgy uses electric energy to effect separation through electrolysis.

Cost-effective mining—and profitable mines—depends very much on getting the metallurgy right, so it’s critically important to everything we do here at RCF.

How did you get started in metallurgy?

My father worked for Highveld Steel and Alloys in South Africa, so I was always exposed to metallurgy growing up. I enjoyed science and maths at school, and I even spent several school vacations working for my dad’s company as a furnace operator producing ferrosilicon.

I studied at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, where I had a bursary (scholarship) from a company called GenGold. Once I completed my studies, to get hands-on-experience, I went and worked for them for several years in various gold mines in and around South Africa. To continue my professional development, I also had a stint in their head office in the projects team, so my first five years were more operational and focused on gold.

I then felt like I needed a change in career, so in 1996 I joined an engineering company called Fluor and moved with them to Australia in 1997, along with my wife and daughter who was 2 months old at the time. I worked in the engineering space for a good ten years, designing and commissioning projects around the globe.

In the next part of my career, I worked for a number of junior mining companies managing feasibility studies in various commodities, including base metals, uranium, and gold. In late 2013 I was approached by RCF, and I’ve now been working here for ten years. I’ve worked across operations engineering, project development, and now, finally, in private equity, so I’ve pretty much covered most of the aspects that you could do in my field.

Do metallurgists only deal with construction and operations, or do they have a role in all the different phases of mining?

As soon as the geologist has decided they’ve got something that should be moved forward, the metallurgist starts doing test work to find solutions for extracting the valuable minerals in the most economically efficient way possible. In fact, metallurgical engineers—who are sometimes called process engineers in the engineering space—are involved across all the phases of mining from scoping studies right through to operations.

Metallurgists work with the geology and mining teams to ensure that samples selected for testwork are representative of ore that will be processed and ultimately develop geo-metallurgical models to help guide the mine planning and processing schedules to ensure value is maximized.

Piloting is required for new or complex processes. There’s a lot of development that goes on with some of the more complex metals, such as rare earths. During the piloting stage, mining companies build a mini plant in a laboratory or even on site, and run larger volumes of samples through it to prove a continuous process and develop the required process data to design the plant.

As we’re doing all this, we’re developing what’s called the process flow sheet and defining how things will be processed. This includes sizing and selecting all the equipment—pumps, tanks, crushers, mills, flotation circuits, and so on—developing the process mass and heat balance, developing process flow diagrams (PFDs), and later as the project moves towards execution, piping and instrumentation diagrams (P&IDs).

Once the project moves into the execution phase, the metallurgist is involved with planning how the process will be commissioned and brought online. During operations, metallurgists play a key role in monitoring the process and ensuring optimal process plant performance is achieved.

Sample Process Flow

How do metallurgical assessments impact key investment decisions at different stages? And how do others at RCF look to you to add or uncover value in the deal?

It depends on what phase the project is in, but when I look at a project in a study phase for example, I’m going to look at all the metallurgical test work that’s been done to see if enough has been done and whether there’s anything that jumps out as something the mining company probably should have looked at more closely. Metallurgical assessments define recovery, reagent usage, material handling properties, and waste product characteristics. I’ll look at the flowsheet they’ve come up with to see if they’re missing anything or if it can be improved upon. On the operations side of things, I’m looking for ways to get more value by reducing operating costs. These are all important factors when assessing the value of a project across all phases of the mining lifecycle.

From your perspective as a metallurgist, what are some of the pitfalls or mistakes investors can make when assessing opportunities in a given phase?

Insufficient metallurgical test work or non-representative test work is a common mistake. Companies often don’t spend enough money on test work in the design stage, meaning that you don’t have enough information about what you’re processing. Often not enough variability testing has been done to understand how things could change, and/or the testing is focused on a global composite rather than a sample that is representative of what will actually be processed in the first one to three years of operation.

It’s a shame because the benefits of having this information once you’re in operation far exceed the cost.

Innovative processes or novel technologies that haven’t been tried before are another area that can cause problems. We saw that in the first high-pressure acid leach circuits that were developed for the nickel industry. They all had major issues with how long it took them to get up and running, and performance was well below what was expected. It’s taken many, many years to get those circuits up and running efficiently.

A lot of that comes back to not enough testing, not enough piloting. A lot of junior mining companies just don’t have the in-house capabilities or the experience to catch everything—and that’s where we can add a lot of value.

Do different metals and minerals require different metallurgical assessments in mining? Are some more complicated than others?

No two projects are ever quite the same, and past projects aren’t necessarily the same as future ones. There’s always something different, and a lot of the easier-to-process ores have been consumed. Now we’re turning to more complex methods of treatment.

As the demand for critical minerals increases, flowsheets to extract and separate these minerals are becoming more and more complex.

Tell us about how you work with the RCF investment teams. Are you generally separate from them, or more closely integrated into what they do?

It’s important to have an integrated approach when working with the investment deal teams. You need to understand what they’re looking for, so communication is important. I don’t just hand off my opinion to the deal team and leave it at that. I like to review the financial models the investment team puts together to make sure all our technical inputs have been understood and incorporated into the model correctly. I want to be sure that operating costs have been captured, that they’ve got fixed costs, variable costs, recoveries, and so forth all incorporated correctly. At RCF we use distributions for recoveries and operating costs as opposed to discrete values so it is also important that these are captured correctly.

What is the hardest part of your job? And what do you like best?

I’d say the hardest part is getting sufficient information to perform a detailed review. Sometimes companies are reluctant to share their intellectual property, so we’ll have to go back and forth requesting information to form an opinion. Sometime the work just hasn’t been done.

Also, the technical team can’t be experts in everything, so we can spend a bit of time sourcing technical experts to assist with our due diligence. You want to find someone who not only knows their stuff but understands how we think and is respected in the mining community.

On the positive side, we spend a fair bit of time traveling to see different projects, so that’s always interesting. I’ve been up to the Arctic Circle a couple of times. I went to Panama and was able to see the new Panama Canal being constructed, which was very cool.

And of course, it’s always great when you’ve worked on a deal, it goes through, and things turn out well. There are projects I’ve literally spent years on, so seeing them come to a good conclusion is very gratifying.

Finally, what is your favorite metal—and why?

I started my career in the gold industry, so I have a leaning towards valuable metals such as gold. I’ve worked in operations for gold, and I’ve designed several gold production plants. I guess you could say I have a special place in my heart for it. But I also enjoy base metals like copper, lead, and zinc as well. (Laughs) It’s hard to pick a favorite.

Important Information

This information should not be deemed to be a recommendation of any specific commodity, company, or security. This material is provided for educational purposes only and should not be construed as research. The information presented is not a complete analysis of the energy transition and/or commodities landscape. The opinions expressed may change as subsequent conditions vary. The information and opinions contained in this material are derived from proprietary and non-proprietary sources deemed by Resource Capital Funds and/or its affiliates (together, “RCF”) to be reliable. No representation is made that this information is accurate or complete. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this material is at the sole discretion

of the reader.

None of the information constitutes a recommendation by RCF, or an offer to sell, or a solicitation of any offer to buy or sell any securities, product or service. The information is not intended to provide investment advice. RCF does not guarantee the suitability or potential value of any particular investment. The information contained herein may not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any investment.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal.