Capital markets are exhibiting a strategic misalignment with growing geopolitical consequences. Investors continue to allocate extraordinary levels of capital to artificial intelligence, data center infrastructure, and digital platforms characterized by limited operating histories, opaque unit economics, evolving competitive dynamics, and unresolved regulatory exposure. At the same time, capital deployment into mining and critical minerals, which are foundational to all technology, industrial capacity, national security, and energy systems, remains structurally constrained despite transparent economics and decades of empirical data.

This paper describes this divergence as the Paradox of Visibility: assets with visible risks and measurable fundamentals are systematically discounted, while opaque technological ventures command valuation premiums. The result is not merely financial inefficiency, but a widening gap between geopolitical necessity and capital allocation.

The technologies shaping economic competitiveness and military capability — artificial intelligence, data centers, electrification, advanced manufacturing, and modern weapons systems — are physically dependent on mining a broad set of critical minerals, along with the vertical integration and processing capacity to make it all happen. Copper, lithium, nickel, rare earth elements, aluminum, graphite, and silver are not peripheral inputs; they are strategic enablers. Their supply chains are increasingly concentrated in jurisdictions that explicitly view material control as an instrument of state power.

Electricity demand associated with data centers and AI workloads is accelerating at rates not observed in modern history. Independent analyses project that data center electricity consumption could more than double by the early 2030s, driven primarily by AI training and inference1. This electricity must flow through copper-intensive transmission networks, be stabilized by lithium-ion battery systems, and be generated by equipment incorporating rare earth permanent magnets. These requirements are dictated by physical constraints rather than policy preference and cannot be substituted at scale within relevant strategic timelines.

Mining investment has failed to respond accordingly. Following the commodity downturn of 2011–2015, global exploration and development spending declined sharply and has not recovered to levels consistent with projected demand growth. The consequences are structural and persistent. Developing new mineral supply typically requires 10–20 years from discovery to commercial production. As a result, today’s capital allocation decisions determine material availability well into the 2030s and 2040s.

This paper examines the scale of electricity demand growth, quantifies associated mineral requirements, evaluates the adequacy of current supply pipelines, and assesses the geopolitical concentration of critical mineral processing. It concludes that substitution, recycling, and efficiency gains do help, but cannot resolve projected supply deficits within policy-relevant or security-relevant timeframes.

The strategic implication is clear. Market psychology has created a persistent mispricing between the digital economy investors celebrate and the physical economy that enables it. Disciplined capital deployed into advanced-stage mining and critical minerals assets, particularly in geopolitically aligned jurisdictions, stands to benefit from a structural revaluation as physical constraints, security imperatives, and state intervention increasingly shape markets.

When financial narratives diverge from material reality, it is material reality that ultimately prevails.

Section I. The Paradox of Visibility: Why Transparency Repels Capital

Investing Amid Opacity: The AI Capital Surge

The acceleration of artificial intelligence investment represents one of the most concentrated capital deployment cycles in modern financial history. Capital has flowed rapidly into companies developing large language models, hyperscale data centers, and advanced semiconductor infrastructure, often in advance of demonstrated profitability or stable business models.

Artificial intelligence represents a genuine technological inflection point with potentially transformative implications for productivity, defense capabilities, and economic organization. What is notable, however, is the scale of investment undertaken despite limited visibility into unit economics, durable margins, competitive equilibrium, regulatory exposure, or long-term technological persistence.

Investors routinely commit capital without clear answers to fundamental questions: the marginal cost of inference, the sustainability of pricing power, the durability of proprietary advantage in the face of open-source competition, and the longevity of today’s hardware architectures. These uncertainties are widely acknowledged, yet they have not materially constrained valuation or capital availability.

Opacity, in this context, has not discouraged investment. It has coincided with it.

Transparency as Deterrent: The Mining Capital Drought

Mining and critical minerals investment presents the inverse dynamic. Here, investors confront a sector characterized by unusually high transparency. Commodity prices are publicly reported with decades of historical data. Feasibility studies disclose capital intensity, operating costs, timelines, and expected returns in granular detail. Proven and probable reserves are reported under strict regulatory standards. Physical markets provide continuous price discovery.

Historical price cycles are treated as predictive rather than contextual. Periods of volatility are extrapolated forward without regard to structural change. The availability of long-dated data encourages retrospective risk attribution, where past downturns are implicitly assumed to govern future outcomes regardless of shifts in demand composition, supply constraints, or geopolitical context.

This dynamic reflects a behavioral bias rather than a rational assessment of forward-looking risk. Visibility is mistaken for fragility. Opacity is mistaken for optionality.

The Strategic Irony

Artificial intelligence systems, data centers, and advanced manufacturing do not operate in abstraction. They are intensive consumers of electricity and, by extension, of the minerals required to generate, transmit, and store it.

Large data centers require thousands of tonnes of copper for power distribution and cooling systems, aluminum for structural components, steel for racks and buildings, and rare earth elements embedded throughout motors, power electronics, and cooling infrastructure.2 AI training workloads impose continuous, high-density power demand that must be delivered across a highly-metallic foundation. In summary, the Cloud is made of metal.

Semiconductor fabrication, the bottleneck of the AI ecosystem, relies on copper interconnects, high-purity silicon, specialty metals, and energy-intensive processing. The electricity required to operate these facilities further amplifies mineral demand across the grid.

The result is a structural contradiction. Capital markets enthusiastically fund technologies whose operation is inseparable from mineral supply while systematically underallocating capital to the development of that supply.

This misalignment is not theoretical. It manifests as delayed projects, constrained grids, rising geopolitical leverage at the processing stage, and growing vulnerability to supply disruption. Mines cannot be brought online on demand. Development timelines measured in decades collide with technology and policy timelines measured in years.

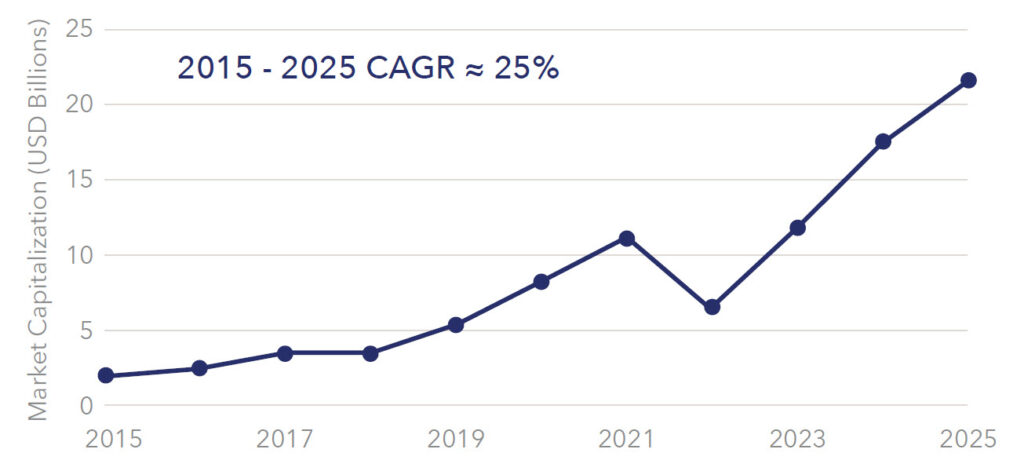

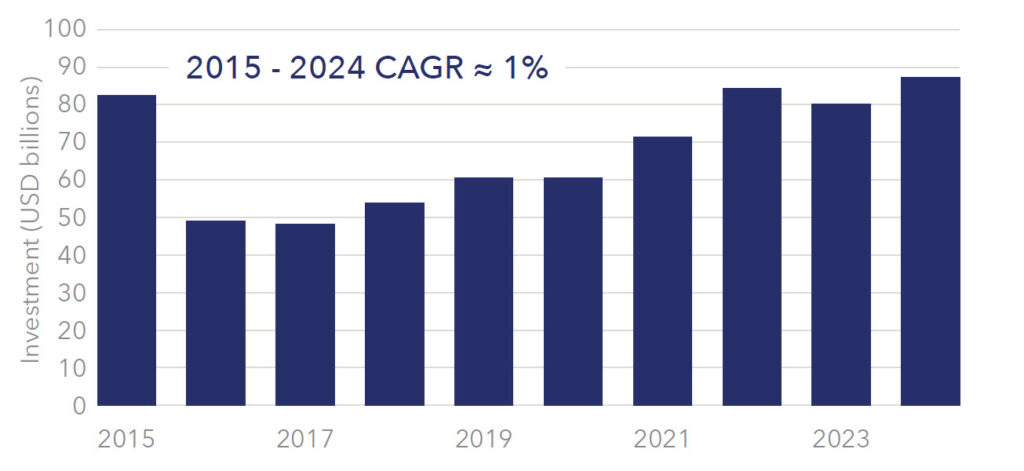

The divergence between financial market valuation and real capital formation becomes visible when downstream digital platforms are compared directly with upstream mineral investment.

Market Valuation of Selected Tech / Compute Platforms

Selected Tech / Compute market capitalization represents the combined market value of leading global technology and compute platform companies, including hyperscale cloud providers and AI infrastructure leaders. The basket includes Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, NVIDIA, Meta Platforms, and Broadcom. Market capitalization figures are based on year-end values sourced from publicly available financial data.

Capital Expenditure in Global Mining (Top 40 Miners)

Source: PwC Mine 2025 Report

Absolute levels are shown; compound annual growth rates are provided for context.

From Market Inefficiency to Strategic Risk

Under ordinary conditions, such a divergence might be corrected through price signals. In this case, the correction mechanism is constrained by physical reality. New mineral supply cannot be accelerated meaningfully through higher prices alone once permitting, engineering, and construction timelines are binding. The consequences of underinvestment are therefore not cyclical but cumulative.

As demand accelerates and supply remains inelastic, the cost of misallocation is transferred from investors to states, industries, and ultimately national security establishments.

The opportunity created by the Paradox of Visibility exists precisely because market psychology discounts transparent fundamentals while ignoring the irreversibility of physical constraints. In environments where material availability determines economic and military capacity, this bias becomes increasingly untenable.

Case Study: 2025 Price Performance

Market signals from a year of scarcity

In 2025, commodity markets experienced a rare convergence of strength. Gold surged approximately 64% to surpass $4,300 per ounce — its strongest annual performance since 1979. Silver shattered records, breaching $70 per ounce for the first time in history with gains exceeding 140%. Copper reached unprecedented levels above $12,000 per tonne on the London Metal Exchange, gaining approximately 37% for its best year since 2009. Steel climbed 27% while aluminum rose 14%.3 45

The simultaneous ascent of precious and industrial metals signaled something more profound than cyclical momentum. The breadth of the rally — spanning materials from wiring to structural components to battery inputs — reflected demand drivers operating across the entire minerals complex.

Physical Constraints, Not Speculation

Unlike previous commodity cycles driven primarily by financial speculation, 2025’s price action stemmed from tangible supply-demand imbalances. Operational disruptions at major mines, including a significant incident at Indonesia’s Grasberg facility, removed an estimated 929,000 tonnes of copper from global supply — physical metal that AI data centers, grid expansion projects, and electric vehicle production required but could not source.6

Exchange inventories revealed the physical tightness. London Metal Exchange copper stocks fell dramatically as buyers withdrew physical metal. Silver inventories at the LME plummeted approximately 75% from 2019 peaks.7 The depletion represented not speculative positioning but actual consumption exceeding production.

Government actions amplified physical market tightness. Tariff policies triggered strategic hoarding as U.S. refined copper imports more than doubled year-over-year to 1.19 million tonnes, while COMEX warehouse inventories surged from 85,000 tonnes to nearly 400,000 tonnes, half of all global exchange stockpiles.8 China intensified export restrictions throughout 2025, imposing licensing requirements on seven rare earth elements and lithium-ion battery components in April, adding five more rare earths by October.9 The Democratic Republic of Congo temporarily suspended cobalt exports.10

Investment Withdrawal Amid Price Strength

Paradoxically, 2025’s price gains coincided with declining investment in future supply. Global investment in critical mineral development rose just 5% in 2025, down from 14% in 2023, barely 2% in real terms after adjusting for cost inflation.11 Lithium exploration budgets fell to roughly half of 2024 levels, described by industry analysts as “absolutely gutted.”12 Start-up funding showed signs of slowdown, with projects involving new entrants most affected by capital scarcity.

Markets priced immediate physical shortage while simultaneously failing to fund the mine development and processing capacity expansion that would alleviate future scarcity. JP Morgan analysts noted: “After essentially flat mine supply growth expected this year, our 2026 mine supply growth estimates have fallen to only around +1.4%, or about 500 kmt lower than our estimates at the beginning of the year.”13 Declining investment today creates inevitable deficits tomorrow.

Inflection Point, Not Peak

Rather than representing a speculative bubble, 2025’s price performance marked what analysts increasingly characterize as an inflection point. The World Bank projects base metal prices will increase through 2027, with copper and tin expected to achieve all-time nominal highs as persistent supply constraints keep markets tight despite subdued global growth.14 Goldman Sachs forecasts batterygrade lithium carbonate climbing to $13,250 per tonne by 2026, driven by rising electric vehicle penetration and the exit of high-cost producers.15 BloombergNEF projects energy storage installations expanding at a 21% compound annual growth rate through 2030.16 Although these estimates are less than 1 month old, demand continues to streak ahead of available supply, with CATL issuing a $17B order for 3.05 million tonnes of LFP cathode material, to be delivered over the next 6 years.17 At only 2 weeks into 2026 and Lithium Carbonate trading at $17,500 per tonne, many 2026 price forecasts are already appearing to be backward looking.

Economic theory holds that prices signal scarcity and thereby attract capital to resolve supply shortages. 2025 demonstrated the signal functioning, yet the capital response remained muted, constrained by the very behavioral and structural factors this paper examines. The gains of 2025 do not represent bubble dynamics destined for correction. They represent the market beginning to price the long-term cost of chronic underinvestment in essential materials.

Section II. The Scale of the Electricity Demand Surge

Electricity demand has become a strategic variable. What was once a question of economic growth and efficiency is now inseparable from national security, industrial resilience, and geopolitical competition. The accelerating electrification of the global economy, driven by digital infrastructure, transportation, industry, and grid expansion, is placing unprecedented strain on generation, transmission, and distribution systems worldwide.

It is the convergence of multiple demand vectors operating simultaneously, each reinforcing the others.

Four Structural Drivers of Electricity Demand Growth

Digital Infrastructure and Artificial Intelligence

Data centers have emerged as one of the fastestgrowing sources of electricity demand in advanced economies. Unlike traditional commercial or industrial loads, AI-driven data centers impose continuous, high-density power requirements with minimal tolerance for interruption.

Independent analyses project that global data center electricity consumption could more than double by the early 2030s, driven primarily by AI training and inference workloads.18 Individual training runs increasingly require tens of megawatts of continuous power, with forward projections reaching gigawatt-scale requirements at single sites within the next decade. These facilities demand not only generation capacity, but grid redundancy, on-site backup systems, and extensive transmission infrastructure.

This material dependence is not abstract.

In multiple jurisdictions, grid interconnection queues for data centers now extend five to seven years, effectively rationing access to power capacity through infrastructure constraints rather than capital availability.19

Transportation Electrification

Transportation electrification represents a second, legally mandated source of demand growth. Major jurisdictions including the European Union, the United Kingdom, several U.S. states, and China have enacted binding timelines for the phaseout of internal combustion engine vehicle sales. These mandates are not contingent on electricity availability; they are statutory requirements.

Electric vehicles shift energy demand from liquid fuels to the grid while materially increasing total electrical infrastructure requirements. Beyond passenger vehicles, electrification is accelerating across buses, commercial fleets, rail systems, and ports. Heavy-duty electric vehicles impose particularly large loads, often equivalent to dozens of households per vehicle during charging cycles.

The result is not substitution but expansion: transportation electrification adds new, inflexible demand to electricity systems already under strain.

Industrial Electrification

Industrial processes are undergoing systematic electrification driven by efficiency gains, emissions constraints, and automation. Heat pumps are replacing hydrocarbon-based heating across residential, commercial, and industrial applications. Advanced manufacturing, robotics, and digitally controlled production lines are inherently electricity intensive.

According to International Energy Agency estimates, industrial motors and process electrification account for one of the largest components of projected electricity demand growth through 2040.20 Unlike consumer demand, industrial electricity consumption is tightly coupled with economic output and national manufacturing capacity, making it strategically sensitive.

Grid Expansion and Energy System Transformation

Regardless of generation mix, electricity must be transmitted and distributed. The expansion of generation capacity, renewable or otherwise, requires extensive investment in transmission lines, substations, transformers, and storage systems.

The International Energy Agency projects that global transmission and distribution infrastructure expansion over the next decade must exceed the pace of the previous ten years by approximately 80 percent. Grid-scale battery storage capacity must increase by orders of magnitude to stabilize increasingly complex and load-intensive systems.

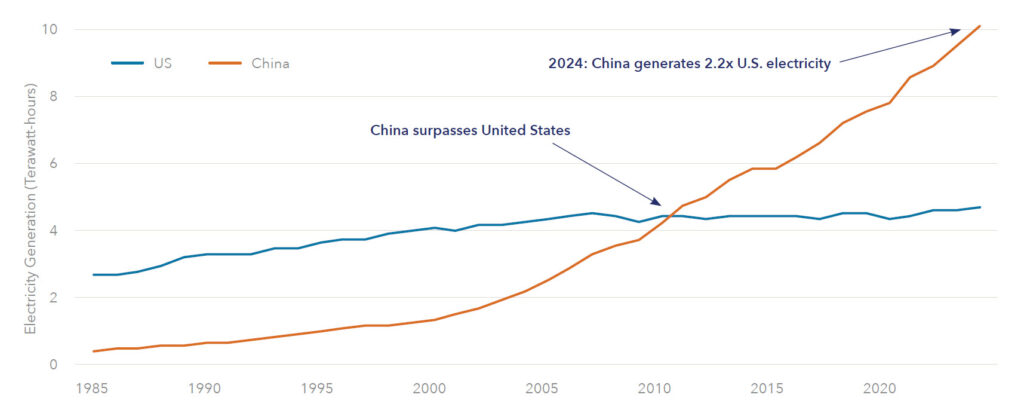

These requirements are additive. Grid infrastructure must expand not only to meet new demand, but to maintain reliability under higher utilization and greater variability. These dynamics are not occurring uniformly across economies; China’s electricity system has expanded at a scale unmatched by any other major industrial power.

The Great Reversal: China vs. United States Electricity Generation

Source: Statistical Review of World Energy Data 2025.

Why This Period Is Structurally Different

Historically, efficiency gains offset much of the growth in electricity consumption. Modern appliances, lighting, and industrial equipment consumed less power per unit of output, flattening demand growth in many advanced economies.

That dynamic has reversed.

Today’s electrification wave introduces entirely new categories of demand such as AI, electric mobility, and grid-scale storage, that did not previously exist at scale. Efficiency improvements continue, but they are overwhelmed by volume growth. Electricity demand is no longer a passive outcome of economic activity; it is a prerequisite for participation in the modern economy.

This shift has direct geopolitical implications. Electricity systems that cannot scale become bottlenecks on economic growth, technological adoption, and defense readiness. Those that can scale gain strategic advantage.

Section III. The Metals Equation: What the Digital Economy Physically Requires

The digital economy is often described as weightless. In reality, it is among the most materially intensive systems ever constructed. Every increment of digital capacity, whether in data centers, electric vehicles, or advanced manufacturing, requires disproportionate quantities of specific metals with no scalable substitutes.

This material dependence is not abstract. It is quantifiable, persistent, and strategically consequential.

The Material Intensity of Electrification

The International Energy Agency has documented a fundamental shift in the material composition of energy and digital systems.21 Electric vehicles require multiple times the mineral inputs of conventional vehicles. Renewable generation and electrified infrastructure require significantly more material per unit of capacity than fossil-fuel-based systems.

Crucially, these minerals are not interchangeable. Each performs a specific physical function that cannot be replicated economically at scale.

| Copper: The Indispensable Conductor | Copper is the backbone of electrification. Its unique combination of electrical conductivity, thermal performance, ductility, and cost makes it irreplaceable across grids, vehicles, data centers, and industrial systems. Electric vehicles contain several times more copper than internal combustion vehicles, with content increasing further for buses, trucks, and charging infrastructure. Data centers require thousands of tonnes of copper for power distribution, cooling systems, and networking equipment. Grid expansion is copper-intensive across transmission, substations, and transformers. No alternative material offers comparable performance across these applications without imposing prohibitive size, weight, or efficiency penalties. |

|---|---|

| Battery Metals: Lithium, Nickel, and Cobalt | Lithium-ion batteries dominate current deployment due to their energy density, scalability, and manufacturing maturity. Lithium is chemically irreplaceable in modern battery systems: its unique electrochemical potential and ionic mobility enable high-voltage, reversible energy storage at densities no alternative chemistry has matched without severe trade-offs. Nickel determines the upper bound of energy density and vehicle range, particularly in applications where mass and footprint constraints are binding, while cobalt provides the thermal stability and cycle durability required to safely operate increasingly nickel-rich cathodes. Although battery chemistries continue to evolve, alternatives such as LFP, sodium-ion, and solid-state systems address niche constraints rather than offering a scalable replacement for lithium-ion architectures. Critically, electrification timelines are governed not by laboratory breakthroughs but by industrial realities: multi-decade mine development cycles, multi-year battery qualification processes, and deeply embedded manufacturing infrastructure. As a result, demand for lithium, nickel, and cobalt is not merely cyclical or policy-driven, but locked into the path of global electrification over the coming decades. |

| Rare Earth Elements: Strategic Materials Without Substitutes | Rare earth elements, notably neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium, are foundational to high-performance permanent magnets that enable the electrification of motion.22 These magnets underpin the most efficient electric motors used across electric vehicles, wind turbines, industrial automation, data-center thermal management, and advanced defense platforms, where power density, reliability, and thermal tolerance are binding constraints rather than design preferences.23 While alternative motor architectures exist, they impose material penalties in efficiency, weight, and size that compound rapidly in power-constrained systems, increasing total energy consumption, cooling requirements, and system costs.24 As electrification scales, these trade-offs become increasingly untenable, reinforcing demand for rare-earth-based magnet systems rather than diminishing it.25 Unlike many other critical materials, rare earths face their most acute vulnerability not at the mining stage but in processing and separation, where supply chains remain highly concentrated and capital-intensive. This concentration creates a structural chokepoint that extends beyond civilian electrification into defense, aerospace, and advanced electronics, where substitution is constrained by performance requirements, qualification timelines, and national-security considerations.26 |

| Supporting Materials: Aluminum, Silver, Graphite, and Silicon | Beyond their individual applications, aluminum, silver, graphite, and silicon occupy structurally non-substitutable positions within the physical architecture of electrification. Aluminum’s conductivity-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance make it uniquely suited for grid expansion and long-distance transmission, where material intensity rises faster than overall power demand. Silver, despite sustained efforts to thrift its use, remains unmatched in conductivity and reliability at the cell level, imposing a hard floor on photovoltaic material requirements as solar deployment scales. Graphite’s crystallographic structure enables lithium intercalation with durability and efficiency that alternative anode materials have yet to replicate at commercial scale, while high-purity silicon forms the technological bedrock of both power electronics and solar generation. In each case, substitution is constrained not by cost alone but by fundamental performance thresholds, manufacturing maturity, and qualification timelines, reinforcing these materials as durable, volume-driven inputs to electrification rather than discretionary commodities. |

Strategic Implications of Material Dependence

Material demand is not a side effect of the digital transition; it is an enabling condition. As electricity demand accelerates and systems electrify, mineral intensity rises faster than output. This creates structural exposure to supply constraints that cannot be resolved through efficiency gains alone.

For states and industries alike, access to these materials increasingly determines the pace of technological adoption, industrial competitiveness, and defense capability. Markets that fail to internalize this reality risk ceding strategic advantage to actors that do.

Section IV. The Supply Reality: A Structural Deficit

If electricity demand and mineral intensity are accelerating as described, the central question becomes whether supply can respond in time.

The global mining industry is confronting a structural deficit driven by long development timelines, declining ore quality, geopolitical concentration, and a prolonged period of capital underinvestment. These constraints are not cyclical and cannot be resolved through price signals alone within policy- or securityrelevant horizons.

The Project Pipeline Gap

Across multiple critical minerals, the currently announced and financed project pipeline is insufficient to meet projected demand through the 2030s. Independent assessments by the International Energy Agency and national geological surveys indicate substantial shortfalls in copper, lithium, nickel, and select rare earth elements even under conservative demand scenarios.27

This gap reflects not a lack of known resources, but a lack of advanced-stage projects capable of reaching production within the next decade. Discovery alone does not create supply. Only projects that progress through feasibility, permitting, financing, construction, and ramp-up contribute material to markets and that progression is increasingly constrained.

Opacity, in this context, has not discouraged investment. It has coincided with it.

The Reality of Mine Development

The development of new mineral supply operates on timelines fundamentally misaligned with modern policy, technology, and capital markets.

Even under favorable conditions, the path from discovery to commercial production typically requires 10–20 years. This includes multi-year exploration programs, resource definition, engineering and feasibility studies, environmental review and permitting, construction, and operational ramp-up.

As a result, decisions made today determine supply availability in the mid-2030s and beyond. Conversely, the underinvestment of the past decade has permanently constrained supply during the current demand acceleration. Time lost cannot be readily recovered.

Declining Ore Grades and Rising Intensity

Compounding timeline constraints is a secular decline in ore quality across many commodities. Average ore grades have fallen steadily over decades, requiring miners to extract and process increasing volumes of material to produce the same quantity of refined metal.28

Lower grades increase capital intensity, operating costs, energy consumption, water usage, and environmental footprint per unit of output. They also raise technical risk and lengthen development timelines. The implication is straightforward: even where resources exist, the effort required to convert them into usable supply is rising.

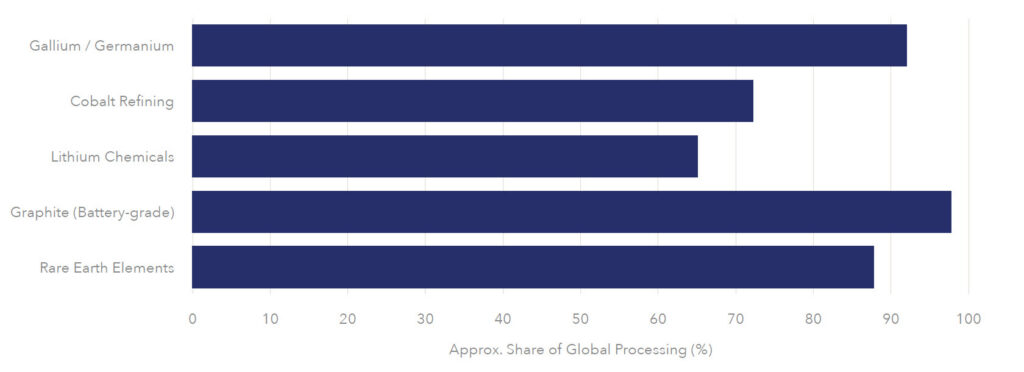

Geopolitical Concentration and Processing Bottlenecks

Perhaps the most strategically significant constraint lies not at the mine mouth, but downstream in processing and refining.

While mineral extraction is geographically distributed, processing capacity, particularly for rare earth elements, battery-grade materials, and specialty metals, is highly concentrated. This concentration introduces chokepoints that magnify the impact of supply disruptions and grant disproportionate leverage to processing jurisdictions.

For many critical materials, processing capacity, not resource availability, defines effective supply.

The Lost Decade of Underinvestment

The commodity downturn following the 2011 peak precipitated a sharp contraction in mining capital expenditure and exploration spending. Balance sheet repair, shareholder returns, and capital discipline replaced growth investment as industry priorities.

This retrenchment coincided with the early stages of the electrification and digital infrastructure buildout. New mining projects that would have entered production in the late 2020s or early 2030s were never initiated. Exploration programs that would have discovered the next generation of deposits were deferred or abandoned.

The result is a structural supply gap that cannot be closed quickly, regardless of price incentives.

Case Study: The China Factor

Processing Dominance as Strategic Leverage

The structural supply deficit is global, but its strategic implications are shaped decisively by China’s position within critical mineral supply chains.

In materially constrained systems, sovereignty resides not with those who extract, but with those who convert. China’s role extends far beyond resource extraction. Over the past two decades, it has systematically consolidated control over midstream processing: the conversion of raw materials into usable industrial inputs. This distinction is decisive.

China’s rapid urbanization and infrastructure expansion in the early 2000s drove unprecedented demand for steel, copper, aluminum, and energy. This demand reshaped global commodity markets and oriented mining investment toward servicing Chinese consumption.

Simultaneously, China invested heavily in refining, smelting, separation, and downstream manufacturing capacity. Environmental tolerance, state support, and long-term industrial planning enabled the construction of processing facilities that Western economies either resisted or dismantled.

By the time Chinese construction demand began to slow, the strategic advantage had already shifted. Control of processing had become a durable source of leverage independent of domestic consumption.

The Processing Chokepoint

Today, China dominates processing capacity across a wide range of critical materials.29 It controls the overwhelming majority of rare earth separation, battery-grade graphite processing, lithium chemical refining, and cobalt refining. For several materials essential to defense systems and advanced electronics, Chinese processing shares exceed 90 percent.30

This dominance extends to “derivative” or byproduct minerals, elements such as gallium, germanium, indium, tellurium, and rhenium that are recovered only during the processing of host metals. By controlling smelting and refining of base metals, China effectively controls supply of entire families of strategically important material.

Exhibit 5 – Global Concentration of Critical Minerals Processing (China)

Strategic Precedent and Coercive Capacity

China has demonstrated a willingness to use material dominance as a policy instrument. Past restrictions on rare earth exports resulted in rapid price escalation and supply disruption, underscoring the sensitivity of markets to processing chokepoints.

Equally important is China’s capacity to deploy countermeasures. Periods of elevated prices have been followed by market flooding, eroding the economics of non-Chinese projects and deterring alternative supply development. This dynamic reinforces concentration and discourages competitive entry.

Western Exposure

For import-dependent economies, the implications are direct. Defense platforms, energy systems, telecommunications infrastructure, and advanced manufacturing all rely on materials processed predominantly outside allied jurisdictions. Permitting, financing, and constructing alternative processing capacity requires many years and sustained political commitment.

In the interim, strategic exposure remains.

The China factor is therefore not one risk among many. It is the central condition shaping the strategic landscape of critical minerals.

Section V. The Policy Paradox: Mandates Without Means

Governments across advanced economies have adopted ambitious electrification and decarbonization mandates. These policies reflect legitimate strategic objectives: reducing emissions, securing energy independence, and maintaining technological competitiveness. Yet they are being implemented alongside regulatory, legal, and political frameworks that constrain the very mineral supply required to meet them.

The result is a policy paradox: outcomes are mandated while inputs are restricted.

Electrification Timelines as Law, Not Aspiration

In multiple jurisdictions, electrification targets are no longer indicative goals; they are binding legal requirements. The European Union, the United Kingdom, several American states, and China have enacted timelines for the phase-out of internal combustion engine vehicle sales. Utilities are required to integrate renewable generation at scale. Industrial emitters face tightening constraints that favor electrified processes.

These mandates create demand certainty. Automakers, utilities, and manufacturers must comply regardless of cost or complexity. Capital investment downstream is therefore compelled by statute rather than market preference.

Supply-Side Constraints as Policy Choice

In contrast, the development of mineral supply is treated as discretionary, subject to lengthy permitting processes, overlapping regulatory jurisdictions, and extensive legal challenge. In the United States, permitting timelines for major mining projects routinely exceed seven to ten years. In Europe, domestic mining is often politically unthinkable despite heavy reliance on imported materials.

This asymmetry is consequential. It is functionally equivalent to mandating agricultural output while restricting access to arable land. Demand is enforced; supply is deferred.

The contradiction is rarely acknowledged in policy design, but its effects are cumulative. Each year of delay compounds future scarcity.

Strategic Implications of Policy Misalignment

From a geopolitical perspective, this mismatch transfers leverage outward. As domestic supply options are constrained, reliance on external processing and refining increases. Import dependence deepens precisely as geopolitical competition intensifies.

Policy mandates that fail to account for material feasibility risk becoming self-defeating. They accelerate dependence on concentrated supply chains while eroding domestic industrial capacity.

The Collapse of Strategic Stockpiles

Few examples illustrate this failure more clearly than the erosion of strategic material reserves.

The United States National Defense Stockpile was established to ensure access to critical materials during periods of conflict or supply disruption.31 At its peak, near the end of the Cold War, the stockpile held materials valued at approximately $22 billion, inflation-adjusted.32 When the Cold War ended, Congress authorized the sale of “excess materials,” and over subsequent decades the stockpile was largely liquidated; its inventory value fell to roughly $888 million by 2021, a reduction of more than 90% on an inflation-adjusted basis.33

Today, remaining inventories are minimal relative to both civilian and defense requirements. This drawdown occurred precisely as critical mineral supply chains became more concentrated and more strategically sensitive.

The implicit policy assumption — that markets alone would allocate materials efficiently under all conditions — has not held.

Section VI. Why Alternatives Won’t Close the Gap

In response to growing concern over mineral scarcity, three solutions are frequently proposed: recycling, substitution, and efficiency. Each will play a role, but none can resolve the projected supply deficit within relevant time horizons.

Recycling: Too Little, Too Late

Recycling is often presented as a circular solution capable of materially reducing primary demand. In practice, recycling is constrained by the size and age of the installed base.

Electric vehicle batteries, grid infrastructure, and data center equipment installed today will not reach end-of-life for ten years to several decades. The material required to build these systems must therefore come from primary supply. Recycling can only recover what already exists, and most of what will be required has not yet been built.

For copper, the constraint is even more severe. Transmission lines, substations, buildings, and industrial systems have lifespans measured in decades. Copper installed to meet near-term electrification goals will not return to recycling streams until mid-century or later.

Recycling can mitigate long-term demand. It cannot solve near-term scarcity.

Substitution: Limited by Physics

Substitution is similarly constrained. Aluminum can replace copper in some transmission applications, but at the cost of increased size, weight, and energy losses. In space-constrained environments — such as, electric motors, data centers, urban grids — these trade-offs are prohibitive.

For rare earth permanent magnets, alternative motor designs exist, but they impose efficiency penalties that scale poorly in power-constrained systems. As electricity availability becomes a binding constraint, efficiency losses translate directly into higher infrastructure requirements elsewhere.

Substitutes exist at the margin. They do not exist at scale.

Efficiency: Overwhelmed by Volume Growth

Efficiency improvements have been substantial and will continue. Yet efficiency gains reduce intensity, not absolute demand. As systems become more efficient, they also become more widely deployed.

Electric vehicles today are more efficient than earlier models, yet average battery sizes continue to increase. Data center computing efficiency improves annually, yet total electricity consumption rises faster due to expanding workloads. Efficiency enables expansion; it does not cap it.

The Timeline Constraint

The binding constraint across recycling, substitution, and efficiency is time. Recycling infrastructure requires years to build and decades to mature. Novel materials require extended development and qualification cycles. Efficiency gains compound gradually.

Policy mandates and strategic competition operate on much shorter timelines. The gap between nearterm demand and long-term mitigation remains.

Implications for Capital and Strategy

The inability of alternatives to close the gap shifts the burden decisively back to primary supply. Absent accelerated investment in mining, processing, and infrastructure, scarcity becomes unavoidable.

In such environments, markets alone struggle to allocate resources efficiently. States intervene, prioritization frameworks emerge, and material access becomes a strategic variable rather than a purely economic one.

For investors, this reality reframes mining and critical minerals not as cyclical exposures, but as foundational assets embedded in national resilience and industrial capacity.

Section VII. The Investment Case: Strategic Capital in a Constrained World

The convergence of accelerating demand, constrained supply, long development timelines, and geopolitical concentration reframes mining and critical minerals investment. This is not a conventional commodities cycle. It is a structural reordering of material value driven by technological dependence and strategic competition.

Under such conditions, capital allocation decisions take on significance beyond financial return alone. They shape industrial capacity, supply chain resilience, and national leverage.

Structural, Not Cyclical

Traditional commodity cycles are characterized by relatively elastic supply responses. Higher prices incentivize production, capital flows into new projects, supply expands, and prices eventually normalize. That dynamic presumes that supply can respond within investment-relevant timeframes.

Critical minerals do not operate under those conditions.

Demand growth is being driven simultaneously by statutory mandates, technological adoption, and security imperatives. Supply responses are constrained by geology, permitting, engineering complexity, and social license. Substitution and recycling cannot meaningfully relieve pressure in the near term. The result is a sustained imbalance rather than a transient dislocation.

In structural deficit environments, pricing power accrues to producers not because of temporary scarcity, but because physical constraints persist regardless of capital availability.

Bottleneck Economics and Strategic Value Capture

In constrained systems, value does not accrue evenly across the supply chain. It concentrates at bottlenecks.

For the digital and electrified economy, these bottlenecks are not application-layer technologies but physical inputs: electricity, transmission capacity, refined minerals, and the assets that produce them. When access to copper constrains grid expansion, or when rare earth processing limits motor production, the marginal value of those materials rises disproportionately.

Scarcity of Permitted, Advanced-Stage Assets

Not all mineral assets are equivalent. Deposits with advanced engineering, secured permits, existing infrastructure, and favorable jurisdictions are genuinely scarce. The universe of projects capable of reaching production within the next decade is limited and shrinking.

These assets exhibit characteristics uncommon in other sectors:

- Operating lives measured in decades

- High barriers to entry

- Inelastic demand

- Strategic relevance that invites state support rather than disruption

As policy frameworks increasingly recognize material constraints, such assets are likely to attract preferential treatment, including expedited permitting, strategic offtake agreements, and public-private financing structures.

Capital Discipline as Strategic Advantage

The prolonged underinvestment of the past decade has imposed discipline across the mining sector. Balance sheets are stronger, project hurdles have risen, and capital allocation is increasingly focused on quality rather than volume.

In a structurally constrained environment, this discipline enhances returns rather than limiting them. Projects that proceed do so into tighter markets with fewer competitors and higher barriers to entry.

For investors, the opportunity lies not in speculative exploration, but in disciplined deployment into assets positioned to come online during peak deficit periods.

Alignment with Geopolitical Priorities

As material constraints become visible, governments are increasingly willing to intervene. Strategic stockpiling, domestic processing incentives, export controls, and priority allocation frameworks are already emerging.

Capital aligned with these priorities benefits from asymmetric support. Assets located in allied jurisdictions, supplying critical infrastructure and defense-relevant applications, operate under a fundamentally different risk profile than discretionary commodity producers.

Mining investment, in this context, is no longer peripheral. It is a component of national resilience.

Section VIII. Conclusion: When Material Constraints Shape Power

The digital economy is not abstract. It is physical.

Future facing technology (AI, Datacenters, and Robotics) is essentially metallic and powered by electricity. Electricity requires metals of all types: steel, copper, aluminum, lithium, nickel, rare earth elements, critical minerals, minor metals (tin, tantalum), and even precious metals (gold, silver and PGMs) to generate, transmit and/or store for future use. These relationships are dictated by physics, not preference. They are not subject to software-style scaling or rapid substitution. The metal inputs are either available, or they’re not.

Yet capital markets continue to allocate resources as if material supply were perfectly elastic, fungible, and geopolitically neutral. This assumption has proven increasingly fragile.

The Paradox of Visibility captures this failure. Transparent, measurable risks are treated as disqualifying, while opaque technological uncertainty is rewarded. The result is systematic underinvestment in the physical systems that underpin economic growth, technological leadership, and national security.

As demand accelerates and supply remains constrained, this misalignment becomes untenable. Scarcity asserts itself. States intervene. Access to materials becomes a determinant of power rather than a background variable.

In such environments, markets do not clear smoothly. They freeze and price signals reflect need, not just fear and greed, propelling price volatility higher.

The implication for investors and policymakers is the same: early recognition of material constraints confers advantage. Capital deployed into critical mineral supply, particularly advanced-stage assets in geopolitically aligned jurisdictions, stands to benefit from structural revaluation as physical reality reasserts itself over financial narrative.

Technology may define the future. But material investment and value chain ownership will determine who gets there.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is provided for educational purposes only and should not be construed as research. The information presented is not a complete analysis of the commodities landscape. None of the information constitutes a recommendation by RCF, or an offer to sell, or a solicitation of any offer to buy or sell any securities, product or service. The information is not intended to provide investment advice. RCF does not guarantee the suitability or potential value of any particular investment. The information contained herein may not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any investment.

This document is not intended to constitute legal, tax or accounting advice or investment recommendations. Individuals should seek advice from their own legal, tax or investment counsel; the merits and suitability of any investment should be made by the investing individual. This document includes forward-looking information, and we caution you that such information is inherently less reliable. These statements may not be representative, or may differ, perhaps materially, from future results. Such forward-looking statements are inherently unreliable as they are based on estimates and assumptions about events and conditions that have not yet occurred and any of which may prove to be incorrect. In addition, the accuracy of such statements are subject to uncertainties and changes (including changes in economic, operational, political or other circumstances or the management of a particular portfolio company), all of which are beyond RCF’s control. There can be no assurance that any such expectations and projections will be attained. RCF undertakes no obligation to update or revise any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.

This presentation contains commodity specific information; this information is provided as an example only. Each commodity will be subject to its own facts and circumstances which may make it more or less likely to align with the examples provided. This information should not be deemed to be an investment recommendation of any specific commodity, company or security.

The market volatility, liquidity, concentrations, restrictions and other characteristics of private market investments are materially different from indices, and therefore the indices do not necessarily reflect a basis for comparison with private market investments. The performance of these indices is reported on the gross performance of the underlying assets and does not take into account any fees or expenses that may be associated with investing in those assets. Any attempt to mimic the indices will result in fees and expenses associated with investing and will reduce performance.

The opinions expressed may change as subsequent conditions vary. The information and opinions contained in this material are derived from proprietary and non-proprietary sources deemed by RCF to be reliable. No representation is made that this information is accurate or complete. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this material is at the sole discretion of the reader.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal.

- International Energy Agency (2024-2025). “Energy and AI” and “Electricity 2025”. ↩︎

- RAND Corporation (2025). “AI’s Power Requirements Under Exponential Growth”. ↩︎

- Investing.com, “Gold Prices Set for 60% Annual Jump Amid Fed Easing”, January 2, 2026. ↩︎

- Yahoo Finance, “Gold and Silver Hit Records in 2025”, December 2025. ↩︎

- Yahoo Finance, “Why copper is on pace for its best year since 2009”, December 30, 2025. ↩︎

- Fastmarkets, “Copper: October’s new all-time highs, a pullback and consolidation is not a surprise”, November 2025. ↩︎

- TradingKey, “Gold Price Steady Climb and the Sudden Surge of Silver and Copper”, December 2025. ↩︎

- TradingKey, “Gold Price Steady Climb and the Sudden Surge of Silver and Copper”, December 2025. ↩︎

- NAI 500, “A historic Rally: Gold, Silver, and Copper Prices Hit Record Highs Simultaneously”, December 2025. ↩︎

- Fastmarkets, “Monthly BRM Update 2025”, November 2025. ↩︎

- International Energy Agency, “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025: Executive Summary”, 2025. ↩︎

- Nasdaq, “Lithium Market 2025 Year-End Review”, December 2025. ↩︎

- Yahoo Finance, “Copper Prices Are Soaring”, December 2025. ↩︎

- World Bank, “Metal Prices Outlook: Supply Constraints, Clean Energy Demand, and Market Risks”, December 2025. ↩︎

- deVere Group, “Lithium Price Outlook 2025: Oversupply Weighs on Prices”, July 2025. ↩︎

- Metalshub, “What’s Driving Lithium Demand in 2025 and Beyond?”, 2025. ↩︎

- Caixin Global, “Battery-Materials Maker Draws Regulatory Scrutiny Over $17B CATL Deal”, 14 January 2026. ↩︎

- International Energy Agency. Electricity 2025; Energy and AI, 2024-2025. ↩︎

- BloombergNEF, Power for AI: Easier Said Than Built, 2024. ↩︎

- International Energy Agency (2019). “World Energy Outlook 2019 – Electricity Sector Analysis”. ↩︎

- International Energy Agency. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, 2021. ↩︎

- International Energy Agency (IEA). The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. Paris: IEA, 2023. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Critical Materials Assessment. Washington, DC: DOE, 2023. ↩︎

- Fraunhofer Institute for Manufacturing Technology and Advanced Materials. “Permanent Magnet Motors vs. Induction Motors: Efficiency and Power Density Trade-offs.” ↩︎

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2024 (Technical Annex). ↩︎

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Rare Earths: Defense Supply Chain Vulnerabilities Persist. Washington, DC: GAO, 2024. ↩︎

- International Energy Agency. Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024. ↩︎

- World Bank. Minerals for Climates Action; Metals Focus ↩︎

- AidData. Power Playbook: Beijing’s Bid to Secure Overseas Transition Minerals, 2025. ↩︎

- Atlantic Council, Issue Brief: Mapping China’s strategy for rare earths dominance, June 13, 2025. ↩︎

- U.S. Congressional Research Service, “Emergency Access to Strategic and Critical Materials: The National Defense Stockpile”, 2023. ↩︎

- Heritage Foundation’s Backgrounder No. 3680, “Revitalizing the National Defense Stockpile for an Era of Great-Power Competition”, January 4, 2022. ↩︎

- Reps. Scott Franklin and Seth Moulton, “Franklin and Moulton Urge House Appropriators to Revive National Defense Stockpile Funding”, April 27, 2022. ↩︎